Thursday, 25 January 2018

Guest lecture, Bradford School of Art, Wednesday 31 January - Bradford’s brutalist masterpieces: William Mitchell’s murals in Bradford, Bingley and Ilkley

Bradford’s brutalist masterpieces: William Mitchell’s murals in Bradford, Bingley and Ilkley

Born in 1925, the artist and industrial designer William Mitchell’s work can be seen in towns and cities around the world. However, it does not hang on the wall of art galleries, but is an integral part of the buildings in which it is found. These range from everyday places such as schools, libraries, pubs, subway underpasses and the foyers of post-war towerblocks, to flagship buildings like Harrods and the Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King in Liverpool.

The talk will give an overview of Mitchell’s work and career, focusing in particular on three artworks by William Mitchell in the Bradford area which demonstrate his post-war work in municipal and civic contexts as well as for corporate and commercial clients. Using innovative techniques and working in media such as moulded concrete and fibreglass, all three murals are distinctively of Mitchell’s style, yet take different stylistic approaches, from abstracted pattern-making to incorporating elements of the history of the area in which they are located.

It will explore a series of concrete murals in Bradford’s Kirkgate market, built in 1973 to replace a previous Victorian market, and carried out by Mitchell or one of his associates; thirteen fibreglass panels, commissioned for the former Bradford and Bingley Building Society headquarters in Bingley in the early 1970s and depicting the architectural and engineering landmarks of the area; and a large mural for the Ilkley Wool Secretariat, completed in 1968, which explores the history of wool manufacture locally.

These case studies will be used to highlight wider changes in attitudes towards post-war architecture, and the ways in which these types of artworks are regarded: whilst a new home has been sought in recent years for the Bingley murals, which were removed as the highly unpopular building in which they were situated was demolished, Mitchell’s Ilkley relief has been widely feted and was celebrated with Grade II listing by Historic England in 2015.

Wednesday, 3 February 2016

Northern Quarter Street art tour, Saturday 13 February (for the Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art)

Next Saturday (Saturday 13 February), the Shrieking Violet will be leading a street art tour to celebrate 30 years since the Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art (formerly known as the Chinese Arts Centre) was established, and to coincide with an exhibition featuring artists from RareKind illustration agency, which opens on Friday 5 February.

The Shrieking Violet calls for an expanded definition of street art, to include not just what we might usually regard as street art, ie that which is covert, transient and wall-based, but to situate street art within a wider context of all art which is publicly visible on the streets of Manchester, from mosaics and architectural adornment to statues and sculptures. Street art is something which we have all seen, and about which most of us have an opinion. The tour will be informal, accessible, flexible and participatory, with participants invited to share, reflect on and challenge their own perceptions and experiences of street art and to disclose any particular favourites in the area. The tour will invite discussion on questions such as: Who gets to decide what is art, and who is an artist? How do works of art on the street influence perceptions of a place, both by the people who live/work there and externally? What is ‘beauty’, and who decides what’s beautiful? Does art need to be beautiful? Can a value be placed on street art?

The tour will visit two distinct areas of Manchester city centre – Chinatown and the Northern Quarter – as part of a broader narrative of change and evolution. Manchester has transformed from an industrial Victorian city to a modern city known for its entertainment, creativity and leisure/shopping opportunities, and this can be read through the art on its streets (or lack of it in certain places). Street art may have different motivations, from self-expression and ownership of spaces to decoration, celebration and commemoration of heritage, but all contribute to the identity, atmosphere and demographic of different areas and show how people have shaped Manchester over time.

This is also a tour of contrasts and comparisons, from public art which is official and council-endorsed, and commissioned from high-profile artists, to gallery-supported initiatives and local businesses promoting local artists, to corporate sponsorship of street art, and street art techniques which have been co-opted for advertising purposes, to that which is unsolicited and illegal.

Tickets cost £7. To book, click here.

Wednesday, 1 August 2012

The Shrieking Violet issue 19 (and third birthday party!)

This edition's cover is by Hannah Bitowski, who lives and works in Liverpool and is based in artist-led gallery the Royal Standard. She works in a variety of media, with a penchant for screen-printing and mask-making. This illustration was inspired by a selection of themes Hannah currently draws from: masks, the abstraction of portraiture, facial geometry and the cosmos – particularly inspired by Johannes Kepler, a 17th century mathematician and astronomer who was infatuated with the idea of God existing in geometry, with all answers of the universe coming from there. Even though his theory of the platonic solid solar system was wrong, Hannah thinks the theory in itself, and his attempt to fit geometry into all things, great and small, is enough to warrant praise. This piece attempts to merge the similarities between ritual and reality, myth with maths.

Here's what you'll find inside:

Manchester-based filmmaker Richard Howe continues his series on mental health in the movies by looking at Jesus' Son, directed by Alison Maclean. Richard is currently editing the film Realitease, which touches on mental health. Watch the teaser at https://vimeo.com/45743438 and tweet Richard about films @rikurichard.

I visited the National Football Museum to find out how it compares to Urbis, and see what it has to offer a non-sports fan.

Anouska Smith, a crafter and maker with a beady eye for sparkly things at www.junkieloversboutique.com, offers a guide to her favourite Manchester tea-places. Spot her somewhere in the Manchester suburbs finishing up those cups of tea or trying to avoid the puddles on the side of the road.

Simon Sheppard has contributed an article about a very eccentric fellow named Pierre Baume. Following a career change, allowing him to indulge his passion for modern history, Simon qualified from Liverpool University as an Archivist in 2008 having previously gaining a BA Hons in History from UCLAN. Simon hails from Bolton, but is currently living in Manchester, where he spends his spare time partaking in his new ‘hobby’, Real Ale. To accompany Simon's article, Manchester-based illustrator, musician and DJ Dominic Oliver has imagined what Baume might have looked like...

Liverpool-based writer and journalist Kenn Taylor, who has a particular interest in the relationship between culture and the urban environment, considers some of the implications of the privatisation and fragmentation of our railway system.

James Robinson is a photographer and dabbling videographer. He studied philosophy in Manchester and now lives in London, where he plays bass for indie pop-rock band Being There. James is very proud to provide the Shrieking Violet with its first animal feature. The title, Perros y gatos, was inspired by a sticker album he bought on a school trip to Spain.

Joe Austin has written a tribute to three post-war murals in London and Coventry, by Dorothy Annan, Gordon Cullen and William Mitchell, and highlights the often-uncertain future of public artworks like these. Joe is a qualified architect, originally from the Midlands but a naturalised Londoner for the last 22 years or so. Joe's interests are wide (his blog best illustrates his scattergun mind), but generally revolve around writing, design, architecture, art, culture and history.

Liz Buckley has reviewed Stanya Kahn's exhibition It's Cool, I'm Good in the Cornerhouse galleries. Liz is an Art History graduate living in Salford, and will be starting an MA in Gallery Studies in September at Manchester University.

Godfrey is a rough excerpt from a novel by Matthew Duncan Taylor that may or may not be published next year. Matthew is a journalist who currently works for the Winsford and Crewe Guardian newspapers. He plays in the south Manchester-based bands Former Bullies and Great Grand Suns. Some short stories he has written can be found at matthewduncantaylor.blogspot.co.uk.

Sarah Hill is a Manchester-based artist, and the founder and creative director of Video Jam. Sarah has written an introduction to the project. If you are interested in getting involved, contact her at sarahfrhill@gmail.com.

Issue 19 finishes with a recipe for delicious apricot and poppy seed bread from Shrieking Violet favourite Bakerie in the Northern Quarter.

Download and print your own copy here. Printed copies can also be picked up from the Working Class Movement Library on the Crescent, Salford, and the Bakerie tasting store (the Hive building), Lever Street, Manchester and Piccadilly Records.

Friday, 23 September 2011

The 'public art' of Ford Madox Brown: Manchester's town hall murals

If there is one building that every visitor to Manchester (not to mention every resident) must see, it's the town hall. A building founded on cotton and industry, it's a working monument to the trade that made Manchester what it was, from the statues of great men that stand in the entrance ways to the bee mosaics laid into its floor to ceilings that are covered in the coats of arms of Manchester's former trading destinations. The architect, Alfred Waterhouse, even aimed to capture the area's history in its architecture through a series of murals, realised as Ford Madox Brown's twelve scenes in the great hall. Unfortunately, unless you've been invited to an event in the great hall, it's unlikely you've made it up close to Brown's great work of public art. Partly this is because, as curator of Manchester Art gallery's new exhibition Ford Madox Brown: Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer, Julian Treuherz, says, “It's in use all the time. It's a working building”, and partly because the public by and large don't know they are allowed to look around the building. Now, as part of the exhibition, the murals will be freely open most Sundays.

If there is one building that every visitor to Manchester (not to mention every resident) must see, it's the town hall. A building founded on cotton and industry, it's a working monument to the trade that made Manchester what it was, from the statues of great men that stand in the entrance ways to the bee mosaics laid into its floor to ceilings that are covered in the coats of arms of Manchester's former trading destinations. The architect, Alfred Waterhouse, even aimed to capture the area's history in its architecture through a series of murals, realised as Ford Madox Brown's twelve scenes in the great hall. Unfortunately, unless you've been invited to an event in the great hall, it's unlikely you've made it up close to Brown's great work of public art. Partly this is because, as curator of Manchester Art gallery's new exhibition Ford Madox Brown: Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer, Julian Treuherz, says, “It's in use all the time. It's a working building”, and partly because the public by and large don't know they are allowed to look around the building. Now, as part of the exhibition, the murals will be freely open most Sundays. When the murals were painted, says Julian, the town hall would have been more accessible (although, he admits, “the very, very poor would not have got through its door”) as it was regularly used as a venue for public meetings. Waterhouse intended art to be an integral part of the building, with murals throughout – though this eventually proved to costly and time-consuming as Brown's murals in the great hall alone took fifteen years to complete.

Commissioning murals for the building at all was, says Julian, an act of “complete daring” by the architect following the failure of similar schemes in the Houses of Parliament (Brown's proposals for the Houses of Parliament murals, which were not chosen, are in the Manchester Art Gallery show) and the Oxford Union which, unsuited the the UK's damp climate, soon faded. Waterhouse learned from this and the preparation for murals in Manchester town hall was carefully thought out. Hot air was installed behind the spaces where the murals would go, and stained glass kept to a minimum, free of flashy colours that would shine onto and distract from the paintings. A Gambier Parry style of spirit fresco was chosen, and the walls prepared so that the pigment would react with the surface of the walls – making them “truly architectural, not easel painting”, says Julian, as “they're meant to tell at a distance in this space”.

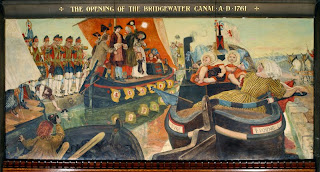

Whilst Waterhouse tried to ensure the murals were a success technically, Brown faced other difficulties. Winning the town hall commission is described by Julian as a 'lifeline' for Brown in the last years of his life, but it was not easy: he suffered from gout and ailments brought about by the cold in the building in winter and a stroke meant the loss temporarily of the use of his right hand. Nor did the council offer their unfailing support, vetoing his plan to end the series of murals with a depiction of the Peterloo Massacre. His painting of the opening of the Bridgewater Canal was also unpopular, with its pomp and circumstance and bright, bawdy colours.

Many of the events in the murals have only a “tenuous link to Manchester” as, explains Julian, “Manchester did not really have a history with lots of heroic events and great personalities.” A Roman Fort is built in Mancenion by a worker writhing with tattoos. Christianity is brought to Manchester following the baptism of King Edwin at York. Closer to home the Fly Shuttle is discovered at Bury, jeered by baying luddites. The world famous scientist John Dalton's discovery of natural gases, a pastoral scene, is overlooked by a curious, almost-cartoonish cow. Brown intended the murals to be 'typical' of Manchester's history rather than 'documentary'. In some cases he even imagines how the future might be, envisaging crowds of children at Humphrey Chetham's school. Animals and children recur throughout the pictures, which are often light-hearted. As Julian says, Brown's paintings are humorous, containing “a lot of fun and wit and satire”. He is “anti-hierarchy and egalitarian” as an artist and “emphasises role of ordinary people, has a lot of fun at the expense of authority figures.” He paints his friends, family and patrons into the pictures – and even himself as the Archbishop of Canterbury.

As the accompanying exhibition at Manchester Art Gallery shows, Brown was in his element as a storyteller. Passionate about literature, he often depicted scenes from Shakespeare and other great works, for example creating series of narrative stained glass windows both for churches and private houses.

Brown believed in “equality between the fine and decorative arts”, designing many of the frames for his paintings, and the exhibition also displays examples of his furniture. He also excelled as a portrait painter, eliciting a candid directness from his sitters, among them Madeleine Scott, daughter of the famous Guardian editor CP Scott, perched atop a then-fashionable tricycle. Another of his most striking paintings, 'Mauvais Sujet (The Writing Lesson)', which depicts a sensuous young girl biting into an apple, her hair in disarray, shows Brown's concern for society: proceeds went to Lancashire Relief Fund to help those affected by the Lancashire cotton famine.

Brown's talent for storytelling and portraiture combine in pictures such as the vivid 'Last of England', where you can see the steely determination on the emigrants' faces, and 'Work', one of his best known paintings. Described by Julian as showing “a humble incident – the type you wouldn't have been allowed to exhibit in the Royal Academy”, it comprises a street scene based around the laying of a sewer in London. Presented is a cross-section of nineteenth century life, from the rich on horseback to workers bent over in toil, right down to the unemployed, beggars and the very poor – those who had to sell wild plants such as chickweed in the street. In the background, layers of advertisements on the wall show the concerns of the time and reflect Brown's interests, including posters for workers' colleges, and the scene is watched over by the social thinker Thomas Carlyle. As Julian explains: “Ford Madox Brown challenged prevailing ideas of what art should be. Victorian artists were governed by decorum. They did not paint life as we saw it in the street.”

Brown's talent for storytelling and portraiture combine in pictures such as the vivid 'Last of England', where you can see the steely determination on the emigrants' faces, and 'Work', one of his best known paintings. Described by Julian as showing “a humble incident – the type you wouldn't have been allowed to exhibit in the Royal Academy”, it comprises a street scene based around the laying of a sewer in London. Presented is a cross-section of nineteenth century life, from the rich on horseback to workers bent over in toil, right down to the unemployed, beggars and the very poor – those who had to sell wild plants such as chickweed in the street. In the background, layers of advertisements on the wall show the concerns of the time and reflect Brown's interests, including posters for workers' colleges, and the scene is watched over by the social thinker Thomas Carlyle. As Julian explains: “Ford Madox Brown challenged prevailing ideas of what art should be. Victorian artists were governed by decorum. They did not paint life as we saw it in the street.”

At £8 for entry, perhaps the Art Gallery show is suited to enthusiasts. But even when the exhibition has finished, the town hall murals are accessible to the public – just ask at the front desk and, as long as there are no events on, you should be able to wander the great hall at your will.

At £8 for entry, perhaps the Art Gallery show is suited to enthusiasts. But even when the exhibition has finished, the town hall murals are accessible to the public – just ask at the front desk and, as long as there are no events on, you should be able to wander the great hall at your will.Ford Madox Brown: Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer, opens at Manchester Art Gallery, Mosley Street, on Saturday September 24 and runs until Sunday January 29 2011. Entry is £8 for adults, £6 for concessions and free for under-18s.

Photos used by permission of Manchester Art Gallery (click for larger images)

Wednesday, 7 September 2011

Meeting William Mitchell (the modernist magazine issue 2)

The maquette for the doors to Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral hangs in the entrance to the Mitchells' flat, which also contains pieces of furniture he made, including two tables in the same style as his mosaic in the Piccadilly Hotel (possibly my favourite Mitchell piece) inset with waste products such as bits of old pianos. "You forget to look at them," said his wife, but the couple kindly moved their furniture around while I took photos.

The maquette for the doors to Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral hangs in the entrance to the Mitchells' flat, which also contains pieces of furniture he made, including two tables in the same style as his mosaic in the Piccadilly Hotel (possibly my favourite Mitchell piece) inset with waste products such as bits of old pianos. "You forget to look at them," said his wife, but the couple kindly moved their furniture around while I took photos. The text below is a slightly longer version of the interview that will appear in Issue 2 of the modernist, accompanied by photos supplied by the Mitchells. the modernist is quarterly publication produced by Manchester Modernist Society. Issues cost £3.75 each — or £15 for a subscription (including postage).

The text below is a slightly longer version of the interview that will appear in Issue 2 of the modernist, accompanied by photos supplied by the Mitchells. the modernist is quarterly publication produced by Manchester Modernist Society. Issues cost £3.75 each — or £15 for a subscription (including postage).Issue 2 will be launched, with wine, at Ferrious (in a converted railway arch on Whitworth Street West) on Thursday September 15 from 6-8pm.

Often, says Mitchell, his artworks used a “very, very involved process”, a challenge to himself to prove they were possible. He remembers: “It was almost an exercise in character building, the artworks were so hard to get to the finish of!” Another unusual use of materials can be seen in the epic mosaic, gleaming with objects such as bottle tops and textured by the addition of gravel, that climbs the full height of the staircase in the Piccadilly Hotel in Manchester's Piccadilly Gardens. Made of bits of furniture and pianos set in resin, Mitchell says "there's a richness to it". It took up the whole of his studio and he had a whole team sanding it down as he wanted to show “there was still the possibility of doing hand craftwork”.

Today, some of Mitchell's works have already been demolished, whereas others are in buildings that have fallen out of favour and face uncertain futures. He's stoical about artworks being lost when buildings are knocked down, although he thinks it's important that “some are kept to give an idea of what the time was like and the type of things you could do”. The social and historical significance of these remarkable artworks is now being reassessed. In Islington, London in 2008, one of Mitchell's works for a school was the first mural of its kind to be listed in its own right, not in the context of the listing of the building to which it was attached. In a library in Kirkby near Liverpool too, a mural has recently been restored and reinstalled. It had languished in storage after the library, ironically, “took it down to be modern”. Those trying (unsuccessfully so far) to get the Turnpike Centre in Leigh listed, which, when it was opened in 1971 featured a new, open-plan library design, also highlight Mitchell's distinctive concrete frieze on the front.

Today, some of Mitchell's works have already been demolished, whereas others are in buildings that have fallen out of favour and face uncertain futures. He's stoical about artworks being lost when buildings are knocked down, although he thinks it's important that “some are kept to give an idea of what the time was like and the type of things you could do”. The social and historical significance of these remarkable artworks is now being reassessed. In Islington, London in 2008, one of Mitchell's works for a school was the first mural of its kind to be listed in its own right, not in the context of the listing of the building to which it was attached. In a library in Kirkby near Liverpool too, a mural has recently been restored and reinstalled. It had languished in storage after the library, ironically, “took it down to be modern”. Those trying (unsuccessfully so far) to get the Turnpike Centre in Leigh listed, which, when it was opened in 1971 featured a new, open-plan library design, also highlight Mitchell's distinctive concrete frieze on the front.