If there is one building that every visitor to Manchester (not to mention every resident) must see, it's the town hall. A building founded on cotton and industry, it's a working monument to the trade that made Manchester what it was, from the statues of great men that stand in the entrance ways to the bee mosaics laid into its floor to ceilings that are covered in the coats of arms of Manchester's former trading destinations. The architect, Alfred Waterhouse, even aimed to capture the area's history in its architecture through a series of murals, realised as Ford Madox Brown's twelve scenes in the great hall. Unfortunately, unless you've been invited to an event in the great hall, it's unlikely you've made it up close to Brown's great work of public art. Partly this is because, as curator of Manchester Art gallery's new exhibition Ford Madox Brown: Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer, Julian Treuherz, says, “It's in use all the time. It's a working building”, and partly because the public by and large don't know they are allowed to look around the building. Now, as part of the exhibition, the murals will be freely open most Sundays.

If there is one building that every visitor to Manchester (not to mention every resident) must see, it's the town hall. A building founded on cotton and industry, it's a working monument to the trade that made Manchester what it was, from the statues of great men that stand in the entrance ways to the bee mosaics laid into its floor to ceilings that are covered in the coats of arms of Manchester's former trading destinations. The architect, Alfred Waterhouse, even aimed to capture the area's history in its architecture through a series of murals, realised as Ford Madox Brown's twelve scenes in the great hall. Unfortunately, unless you've been invited to an event in the great hall, it's unlikely you've made it up close to Brown's great work of public art. Partly this is because, as curator of Manchester Art gallery's new exhibition Ford Madox Brown: Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer, Julian Treuherz, says, “It's in use all the time. It's a working building”, and partly because the public by and large don't know they are allowed to look around the building. Now, as part of the exhibition, the murals will be freely open most Sundays. When the murals were painted, says Julian, the town hall would have been more accessible (although, he admits, “the very, very poor would not have got through its door”) as it was regularly used as a venue for public meetings. Waterhouse intended art to be an integral part of the building, with murals throughout – though this eventually proved to costly and time-consuming as Brown's murals in the great hall alone took fifteen years to complete.

Commissioning murals for the building at all was, says Julian, an act of “complete daring” by the architect following the failure of similar schemes in the Houses of Parliament (Brown's proposals for the Houses of Parliament murals, which were not chosen, are in the Manchester Art Gallery show) and the Oxford Union which, unsuited the the UK's damp climate, soon faded. Waterhouse learned from this and the preparation for murals in Manchester town hall was carefully thought out. Hot air was installed behind the spaces where the murals would go, and stained glass kept to a minimum, free of flashy colours that would shine onto and distract from the paintings. A Gambier Parry style of spirit fresco was chosen, and the walls prepared so that the pigment would react with the surface of the walls – making them “truly architectural, not easel painting”, says Julian, as “they're meant to tell at a distance in this space”.

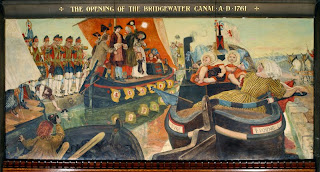

Whilst Waterhouse tried to ensure the murals were a success technically, Brown faced other difficulties. Winning the town hall commission is described by Julian as a 'lifeline' for Brown in the last years of his life, but it was not easy: he suffered from gout and ailments brought about by the cold in the building in winter and a stroke meant the loss temporarily of the use of his right hand. Nor did the council offer their unfailing support, vetoing his plan to end the series of murals with a depiction of the Peterloo Massacre. His painting of the opening of the Bridgewater Canal was also unpopular, with its pomp and circumstance and bright, bawdy colours.

Many of the events in the murals have only a “tenuous link to Manchester” as, explains Julian, “Manchester did not really have a history with lots of heroic events and great personalities.” A Roman Fort is built in Mancenion by a worker writhing with tattoos. Christianity is brought to Manchester following the baptism of King Edwin at York. Closer to home the Fly Shuttle is discovered at Bury, jeered by baying luddites. The world famous scientist John Dalton's discovery of natural gases, a pastoral scene, is overlooked by a curious, almost-cartoonish cow. Brown intended the murals to be 'typical' of Manchester's history rather than 'documentary'. In some cases he even imagines how the future might be, envisaging crowds of children at Humphrey Chetham's school. Animals and children recur throughout the pictures, which are often light-hearted. As Julian says, Brown's paintings are humorous, containing “a lot of fun and wit and satire”. He is “anti-hierarchy and egalitarian” as an artist and “emphasises role of ordinary people, has a lot of fun at the expense of authority figures.” He paints his friends, family and patrons into the pictures – and even himself as the Archbishop of Canterbury.

As the accompanying exhibition at Manchester Art Gallery shows, Brown was in his element as a storyteller. Passionate about literature, he often depicted scenes from Shakespeare and other great works, for example creating series of narrative stained glass windows both for churches and private houses.

Brown believed in “equality between the fine and decorative arts”, designing many of the frames for his paintings, and the exhibition also displays examples of his furniture. He also excelled as a portrait painter, eliciting a candid directness from his sitters, among them Madeleine Scott, daughter of the famous Guardian editor CP Scott, perched atop a then-fashionable tricycle. Another of his most striking paintings, 'Mauvais Sujet (The Writing Lesson)', which depicts a sensuous young girl biting into an apple, her hair in disarray, shows Brown's concern for society: proceeds went to Lancashire Relief Fund to help those affected by the Lancashire cotton famine.

Brown's talent for storytelling and portraiture combine in pictures such as the vivid 'Last of England', where you can see the steely determination on the emigrants' faces, and 'Work', one of his best known paintings. Described by Julian as showing “a humble incident – the type you wouldn't have been allowed to exhibit in the Royal Academy”, it comprises a street scene based around the laying of a sewer in London. Presented is a cross-section of nineteenth century life, from the rich on horseback to workers bent over in toil, right down to the unemployed, beggars and the very poor – those who had to sell wild plants such as chickweed in the street. In the background, layers of advertisements on the wall show the concerns of the time and reflect Brown's interests, including posters for workers' colleges, and the scene is watched over by the social thinker Thomas Carlyle. As Julian explains: “Ford Madox Brown challenged prevailing ideas of what art should be. Victorian artists were governed by decorum. They did not paint life as we saw it in the street.”

Brown's talent for storytelling and portraiture combine in pictures such as the vivid 'Last of England', where you can see the steely determination on the emigrants' faces, and 'Work', one of his best known paintings. Described by Julian as showing “a humble incident – the type you wouldn't have been allowed to exhibit in the Royal Academy”, it comprises a street scene based around the laying of a sewer in London. Presented is a cross-section of nineteenth century life, from the rich on horseback to workers bent over in toil, right down to the unemployed, beggars and the very poor – those who had to sell wild plants such as chickweed in the street. In the background, layers of advertisements on the wall show the concerns of the time and reflect Brown's interests, including posters for workers' colleges, and the scene is watched over by the social thinker Thomas Carlyle. As Julian explains: “Ford Madox Brown challenged prevailing ideas of what art should be. Victorian artists were governed by decorum. They did not paint life as we saw it in the street.”

At £8 for entry, perhaps the Art Gallery show is suited to enthusiasts. But even when the exhibition has finished, the town hall murals are accessible to the public – just ask at the front desk and, as long as there are no events on, you should be able to wander the great hall at your will.

At £8 for entry, perhaps the Art Gallery show is suited to enthusiasts. But even when the exhibition has finished, the town hall murals are accessible to the public – just ask at the front desk and, as long as there are no events on, you should be able to wander the great hall at your will.Ford Madox Brown: Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer, opens at Manchester Art Gallery, Mosley Street, on Saturday September 24 and runs until Sunday January 29 2011. Entry is £8 for adults, £6 for concessions and free for under-18s.

Photos used by permission of Manchester Art Gallery (click for larger images)